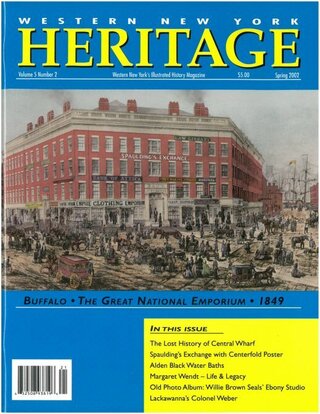

CENTRAL WHARF 1868: Crowds gathered on the wharf and its galleries to view a new steam-powered canal boat. The two buildings with fringed awnings in the center of the photo contain the Board of Trade. Note the large windows along the length of the second story thoroughfare.

WNY Heritage Collection

(This is the second part of a three-part story. Find Part I here.)

The earliest building on the Buffalo River at the foot of Main Street was the wood frame store built by Winthrop Fox in 1814. At No. 1 Main Street, it became the site of “The Rough & Ready” building and Hand’s tugboat office. On the Central Wharf side 50 feet from Main Street was the Old Red Warehouse built in 1816 and in 1825 housing the operations of John Scott, Buffalo’s first “forwarder.” The development of the area that became the Central Wharf began with the establishment of the Erie Canal terminus. Thaddeus Joy recounted the story for a Buffalo audience in an address delivered to the Buffalo Board of Trade in 1848. He refers to the absentee owners of the area between the foot of Main Street and the mouth of the Little Buffalo Creek as “two gentlemen at the east,” one in New York and one in Boston. More specifically they have been discovered to be James Lloyd of Boston and Nathaniel Prime of New York City. Joy worked with a surveyor to lay out Prime and Lloyd Streets and 30-foot-wide building lots. He relates that it was the year the canal opened that he, in partnership with Mr. Webster, built the Joy & Webster warehouse on the east side of the Canal Basin (Commercial Slip). At the same time, he says he cut the Prime slip and wharfed up the creekfront.

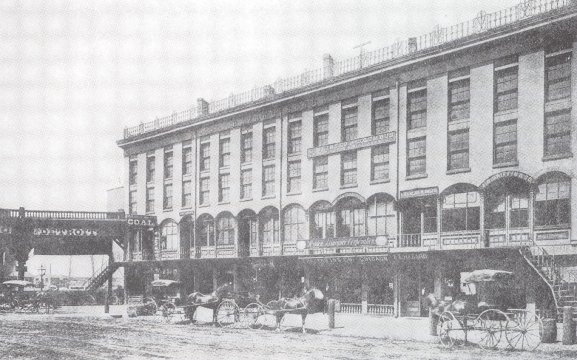

THE HAZARD BLOCK: The triangular-plan anchor block of the Central Wharf, The Hazard Block, built in the 1840s, fronted on both Main Street and the Buffalo River.

Bliss Photo courtesy of the Buffalo & Erie County Public Library

In the 1830s all the lots in that area of the waterfront that would eventually be called the Central Wharf were occupied by wooden buildings. In 1837 the city rebuilt the wooden wharf as a public thoroughfare. The wooden buildings were gradually replaced with brick structures. Built about the time the Central Wharf received its name, the four-story brick Hazard Block at the foot of Main Street had frontage on both the Central Wharf and Main Street. The Hazard Block was the most distinctive and refined piece of architecture on the wharf. The four-story brick building was triangular in plan, taking advantage of the acute angle of its corner site. It had a row of large glass storefronts at street level, sheltered under the projection of a second story iron-railed gallery. The gallery, reached by exterior iron stairs at each end, served as the elevated sidewalk to the second story storefront offices which were distinguished by a series of broad-arched windows that created a nearly continuous wall of glass and natural light. The cornice of the block and the gallery were trimmed with an elegant wrought-iron filigree railing. (A public pass-through provided a shortcut connecting Main Street with the wharf.)

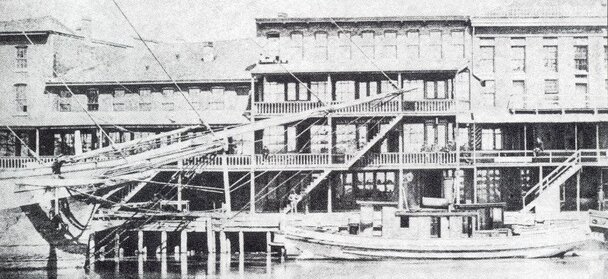

CENTRAL WHARF: A rare 1870s shipboard view of the Wharf. The bowsprit of a large sailing vessel extends across two buildings.

Courtesy Harvey Holzworth

The same features were carried on the wharf side of the Hazard Block, namely the continuous elevated walkway and the large high arched second story windows; eventually they set the character of the entire Central Wharf. When the Board of Trade moved onto the Central Wharf in 1859, they first occupied offices in the second story of the Hazard Block. When they moved to the center of the Central Wharf soon after in 1862, the continuous balcony and the window wall view of the water had become a necessity. The Board of Trade, organized to facilitate and foster local commercial enterprises in 1844, was originated by Russell Heywood, a poor boy who had made good in the grain business. To house this organization Heywood built the Merchants Exchange Building on the east corner of Prime and Hanover Streets, behind the Central Wharf. This building, built the same year as Spaulding’s Exchange, was called “one of the finest buildings in the city.” Unfortunately, no photograph of the building is known to have survived; it is represented in an 1863 birds-eye view.

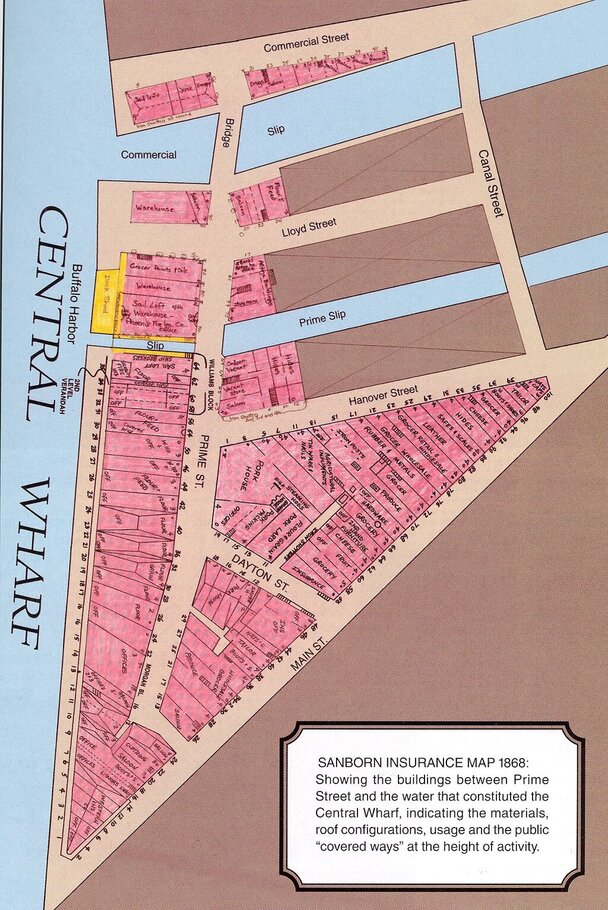

SANBORN INSURANCE MAP 1868: Showing the buildings between Prime Street and the water that constituted the Central Wharf, indicating the materials, roof configurations, usage and the public "covered ways" at the height of activity.

Composite Map created by Judy Pellegrino

The first story of Heywood’s building was occupied by stores fronting on Prime and Hanover Streets, and the entrance stair halls up to the exchange room. The center of the upper three floors of the four story building was one large room, the exchange rotunda. The floor of the rotunda was in the shape of an elongated octagon, 30 by 60 feet, with offices of various sizes opening off its perimeter. A railed gallery around the inner periphery of the rotunda provided access to similar offices off the main room one story up. Above the gallery level the walls of the eight-sided room arched inward to form a dome terminating in a large oblong skylight. The open rotunda had a decorative “tessellated” marble floor. The plaster walls had frescoed designs with buffalos over the doors at each end of the exchange room. Busts of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster were part of the décor. The Board of Trade had offices off the floor of the exchange and held their sessions in the rotunda. The Board of Trade held its first meeting in this building in 1845. It was to promote commerce by serving as a clearing house of information about goods, vessels and people. Its bulletin board advertised the arrivals and departures of vessels. The loss of a vessel was announced with the ringing of a gong. Its reading room had newspapers from all the major cities. The first Morse Telegraph office in Buffalo was located in this building. Samples of grain available for purchase and shipment were on daily display in special bins provided for that purpose. Runners regularly brought guest register lists from all the hotels so that businessmen, and bill collectors, would immediately know who was in town.

CENTRAL WHARF 1863: A detail of the Mangus 1863 birds-eye view of the Buffalo Waterfront. The Prime Slip remains open. Russell Heywood's Merchants Exchange is visible on the Prime Slip behind the Central Wharf.

From the original, preserved in the offices of Phillips, Lytle, Hitchcock, Blaine & Huber LLP

When the Board of Trade relocated onto the Central Wharf there was an increase in business activity creating a demand for offices along the connecting gallery. Located in the center of the Central Wharf, the Board of Trade became the center of activity during the Wharf’s heyday in 1860s and 70s. The entire grain trade business, for which the Port of Buffalo was famous worldwide, was conducted on the Central Wharf. Big deals were hatched and fortunes were made on those balconies. The biggest deal of all was the one that brought the wharf to an abrupt end. In 1882 the Board of Trade built a new building uptown on Seneca Street making way for the railroad to take over the entire old Central Wharf. In 1883 the railroad took the public by surprise with a well-organized conspiracy, laying a track bed down the center of Prime Street in the middle of the night. Over 200 workers were used to accomplish the feat, which was organized like a military operation. Morning found a locomotive in the street where there had been no track the day before. In 1883 the Hazard Block was also demolished by the Delaware Lackawanna & Western Railroad to lay multiple tracks. The railroad takeover marked the end of public access to the waterfront in that area. A suit was brought by the City against the D.L.&W. claiming that the dock had always functioned as a public thoroughfare. Powerful, well-connected lawyers (John Milburn, Louis Babcock, Franklin Locke) prevailed in court for the railroad. But the damage had been done and the historic wharf was gone.

(Continue to Part III.)