At the turn of the century one hundred years ago, one of the most popular pieces of literature in America was Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward 2001-1887. The tour de force, futuristic novel set in the year 2000 was a powerful critique of society and economics. John Dewey in 1935 classed it as one of the three most influential works of the previous half century. Early in the book a character comments that it is easy to look backward over a hundred years but difficult to look forward a few years.

One hundred years have passed since the Pan-American Exposition presented its tangible fictions of an ideal future Rainbow City, conjured up on an empty canvas and as quickly dissolved like Prospero’s “insubstantial pageant faded.” Yet we are still wrestling with its significance. It sought to celebrate the triumphs of industrialized society in the Western Hemisphere, while providing the spectator with an awe-inspiring experience of the sublime. Yet it was loaded with rooted contradictions like the apparently substantial monuments of virtuoso architecture built of chicken wire and staff. The architecture of European absolutism was invoked to celebrate the imperial triumphs of a democracy and its presumptions of progress in civilization; and it was indeed an awe-inspiring achievement.

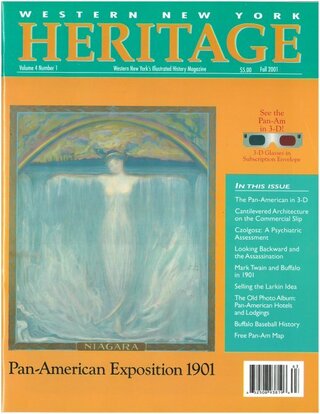

The Pan-American poster painting by Evelyn Rumsey Cary the “Spirit of Niagara” captures the spirit of sublimity in nature as a woman with outstretched arms emerging from the cataract. It is based, in pose and composition, on a drawing in the Louvre by the Mannerist artist Rosso Florentino, with a different emotional connotation. The woman is “Madonna della Misericordia” (Our Lady of Sorrows.) From her outstretched arms cascade a suffering humanity.

The convergence of elation and misery at the Pan-American culminated in the treacherous act of one drab desperado nobody who succeeded in deliberately co-opting the entire rainbow celebration to serve as the mere backdrop and stage-setting for his dramatic final act. To do so he subverted the universal gesture of democratic friendship, the handshake, into a weapon of treachery.

Dare we, one hundred years later, inquire into the human emotions of the assassin? Who cares? Leon Czolgosz set himself a dangerous mission, a “forlorn hope” of his own making. A factory worker resentful of social injustices, disillusioned with the American dream, he characterized himself as a living dead man. Modern philosophy from Kierkegaard to Sartre has shown a fascination for the individual without hope, to the extent of implying that only with the experience of despair does one become fully human. Dostoevsky’s brooding, self-conscious “underground man,” a characterless nobody, was a Czolgosz type. Leon was neither an intellectual nor a criminal, but a desperate man with a dangerous plan to bring his existence to an appropriate conclusion. A few months after the execution of Czolgosz, a detective retracing the assassin’s movements to Cleveland found a book among some pamphlets and papers stashed by Leon in an attic cubbyhole. The investigator purchased the well-thumbed book from Waldek Czolgosz, who said his brother Leon had been studying that book for seven or eight years. It was Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward.

The Pan-American was without question a shining moment in the one hundred year progress of Buffalo from an undeveloped wilderness to a city of world prominence. The fair was a spectacular design accomplishment, and an extravagant celebration of western civilization as it naively marched, full of hubris and prejudice, with pomp and flourish to the tune of a Sousa march, into the bloodiest, most destructive and inhumane century of all. The Exposition is not separable from the assassination. There was a lot at stake in not successfully protecting the President here. McKinley lost his life, the country lost a President and Buffalo lost the celebration.

The story of the Pan-American is a complex story of high expectations and dismal disappointments. The centennial is not something to celebrate but something “to observe” with the dispassionate irony “looking backward” can afford.