Just after Joseph Ellicott laid out the village of Buffalo, Thomas Jefferson signed into law on March 5, 1805 an act of Congress designating the tiny settlement an official Port of Entry (POE). Since tariffs were the sole source of federal revenues in the early years of our fledgling republic, a POE designation for this region was significant. As the official port for most everything headed east, Buffalo was positioned for a century of spectacular growth.

Not, however, without some major calamities and growing pains. The War of 1812 brought devasting violence to both sides of the Niagara River. Within a year the Treaty of Ghent officially ended the war and Buffalo continued its slow growth as a frontier outpost.

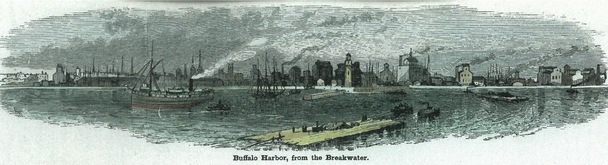

It was not until the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 that the Port’s rise accelerated. During the canal’s first two decades, Erie County exploded with over 60,000 residents, a quarter of them inside the city limits. The number of lake vessels was increasing exponentially. The port of Buffalo boomed with tens of thousands of passengers heading west weekly, and goods bound for the East Coast via the Erie Canal returning.

As Buffalo moved into the second half of the 19th century it was truly the Queen City of the Lakes. Products of every kind from the areas abutting the Great Lakes and the Midwest, found their way east through Buffalo.

Anthony Trollope, surveying American culture for the British Postal Authorities, saw the region as the promised land: “In 1861 I was at Buffalo. I saw the wheat running in rivers, rivers of food running day and night. I saw the men bathed in grain, I felt myself enveloped in a world of breadstuff. I began to know what it was for a country to overflow with milk and honey, to be smothered by its own riches.”

Buffalo’s strength as a crossroads for trade – the “Gateway to the West” – was enhanced by the railroads as the region boomed through the turn of the century and well into the mid-1900s.

Toward the end of the 19th century, John Albright, a local businessman, reasoned that it made no sense to ship iron ore from the Port of Buffalo to Scranton, Pennsylvania, his family’s hometown, to meet the coal. He decided moving the Lackawanna Iron & Steel Mill from Scranton to the shores of Lake Erie could bring coal from the east, meet iron ore from the west and then be perfectly located to ship the finished product to a much larger area at lower cost.

Albright understood the region’s advantages. He knew the location and transportation infrastructure would give the mill a competitive advantage in delivering its products. By the 1950s, however, our leaders had lost sight of Albright’s vision. They did not foresee the need to focus on the core value that our continental crossroads location provides.

Some say the region was blindsided by the St Larence Seaway. Some contend that there was widespread belief that the Seaway would bring ocean-going traffic into the Port of Buffalo. While there may have been those gullible enough to take that view, history does not support it. The political leaders at the state and federal level did everything in their power to derail the Seaway. They did manage to delay it for a time, a course that was as shortsighted as it was futile. What nobody did was think like John Albright. No one thought about how to best use our greatest advantage: location, location, location.

The drastic reductions in waterborne traffic masked dramatic growth in traffic through the Buffalo Port of Entry. We all noticed the stream of trucks crossing our bridges, but it did not occur to most that they were being processed through our port just as goods had earlier been processed though our port as they were transferred from lake freighters to canal barges and rail cars.

As our trade with Canada grew, so grew the POE. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) shifted trade with our friends across the border into high gear. Today Canada is America’s largest trading partner by margins that dwarf the next largest (Mexico), let alone any overseas nation.

Goods flow through our port not just from Canada, but from the Pacific Rim via rail from Vancouver’s seaport. Goods from Europe come via rail from seaports in Montreal and Halifax, the fastest and most cost-efficient routes into the United States. The volume of trade moving through the Port of Buffalo has made it one of the largest among the 301 official POEs in the country – larger than anyone could have imagined 200 years ago.